Maybe Fleetwood Mac will scare our kid away from drugs

Nothing about their story romanticizes cocaine, right?

This is the third installment of an as-yet-untitled series in which I manfully explain music to a nine-month-old baby. Here are the previous entries:

It is never too early to start mansplaining music to a girl (February 2025)

For some reason our baby isn’t responding to Tom Waits (March 2025)

People keep pointing out that I am older than usual for a first-time parent. Statistically that is true, although I don’t care for the insinuation. I would argue instead that anybody who has children in their 20s or 30s is too fucking young. I don’t have data, but if you are reading this, your parents were probably in the typical age range, right? Well, how did it all turn out? Did they compensate for their own parents’ deficiencies and not damage you in similar ways? How is therapy going?

I understand, though, why it is common to have kids earlier in life. Some of the advantages are obvious. For example, a smaller generational gap makes it easier for parents and their kids to share interests and have tastes that overlap, particularly when it comes to music. My best friend and college roommate accidentally became a father when he was 24, before his own prefrontal cortex had even finished forming, and his son never assumed his dad’s favorite bands were stale or corny just because of their age difference. To this day, they argue about Weezer and Green Day albums whenever the kid comes back from college.

When my own daughter goes off to school — assuming higher education still exists and is accessible and is not entirely subservient to rightwing interests — I’ll be around 60. Will we even be able to have a conversation about music that will make sense to either of us? Will Taylor Swift have collapsed into her late-Madonna phase? Will historical revisionists decide all ‘90s guitar music should be classified as butt-rock? Will Kendrick Lamar be emptying a colostomy bag onto Drake’s literal grave?

It is safe to assume that the popular culture of our daughter’s late teen years will be, at best, only faintly legible to me. How, then, will we connect over music in a way that honors its role in my life? My strategy thus far has been a form of immersion therapy, in which I cram her tiny head full of esoteric music-trivia facts, nonsensical genre biases and aggressive but indefensible opinions about bands that will mean nothing to people her age. The goal is to manufacture a precocious music nerd whose first spoken sentence might be a pointlessly contrarian take on a popular artist or record label.

So our dad-daughter solo time thus far has been devoted almost exclusively to lectures about some of the albums in the hoarder-ish LP collection I have amassed, each of which represents between five and forty dollars that otherwise might have been put toward her future in a more material sense, which is the long-term price she will pay for being conceived by a former record-store clerk.

We’re making progress. The work is mysterious and important. Below is my latest effort, transcribed from memory.

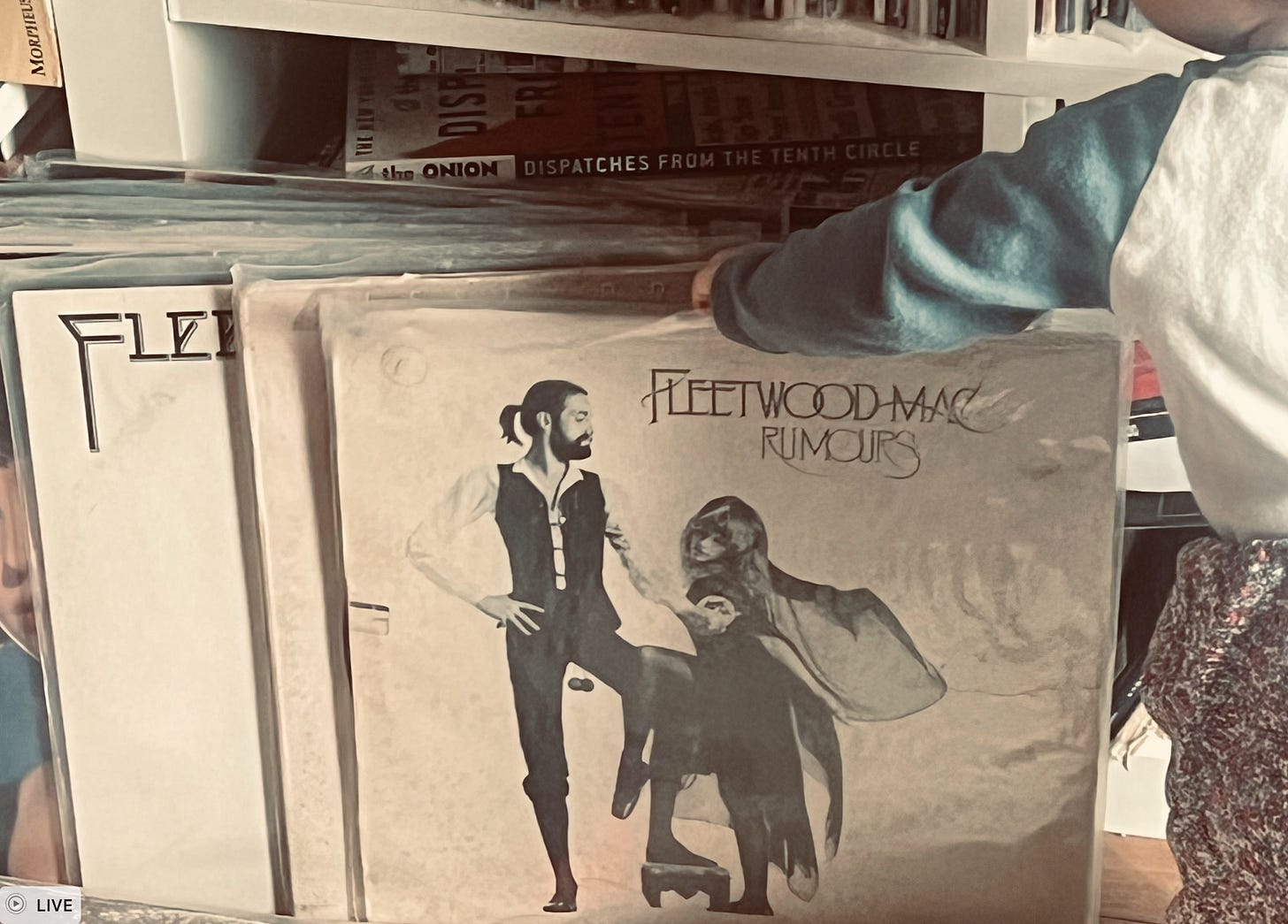

Fleetwood Mac: Fleetwood Mac (1975); Rumours (1977); Tusk (1979)

As your father, I am supposed to warn you about drugs. A drug is any external chemical substance that alters a person’s experience of the world. Drugs are taken either for medicinal or recreational purposes. They can be obtained for a variety of reasons and from a variety of sources. There is the kind that a doctor prescribes and you get at a pharmacy, as well as the type that you might buy through a Venmo transaction falsely labeled “dinner” from a guy who’s hiding an illegal collection of exotic reptiles in the off-campus apartment complex with the lowest rent.

You are going to grow up hearing a lot of boring and morally incoherent messaging about why you should avoid certain recreational drugs. The more you are told not to do drugs by authority figures, the more appealing those drugs will seem. Likely the scare tactics won’t work on you, just like they didn’t work on your dad.

When he was a kid, your dad saw countless TV commercials that were sponsored by the Partnership For a Drug-Free America, including the famous “This is your brain on drugs” ad that showed an egg, representing the brain, cracked into a sizzling skillet. Later, while on drugs, your dad got his mind “blown” when he was told by another person on drugs that the Partnership For a Drug-Free America was actually a lobbying organization that was funded by the pharmaceutical industry, which had a commercial interest in keeping narcotic substances like marijuana illegal so people would have to continue buying synthetic painkillers that had similar effects. Then your dad and his friend both exhaled huge clouds of smoke and got back to watching children’s movies on mute and pointing out coincidental synchronicities to progressive rock albums.

The point is that most of the people who tell you things like “Say no to drugs” are hypocrites, even if their advice is sometimes sound. That includes your dad, who is pretty square these days but did an amount of drugs when he was younger that could be accurately described as “considerable.” Not staggering or inhuman…just considerable.

In general, he was a weed guy, which he is comfortable admitting now that marijuana is legal in about half the country and exists in a mind-shattering form unrecognizable to anyone who has ever spent a weekend night scraping resin from the bottom of a glass bowl with a paper clip. So now that the same people who were desperate to suppress weed have figured out how to monetize it, most of the drug-war scaremongering involves other common illegal inebriants that your dad will NEITHER CONFIRM NOR DENY he has ever engaged with directly. These include opiates, empathogens, psychedelics and stimulants such as amphetamines and a substance called cocaine, which is what we’re going to talk about today.

A hell of a drug

Cocaine is a powder that you inhale through your nose. Its effects include lowered inhibitions, a temporary boost of energy and an increased chance of agreeing to start a business with a person you just met in the bathroom of a dance club. It is responsible for a lot of unfortunate stuff, such as the international cartel economy, the incongruous proliferation of Scarface posters in midwestern college dorms and everything that has ever happened on Wall Street. (The long-term financial strategy for most Americans is allowing their life savings to be managed and invested by an entire industry of people whose hearts are about to explode from cocaine use). Signs a person is abusing cocaine include shaking hands, a bloody nose and frequent mentions of their Soundcloud page. It also might explain why you’ll sometimes see lightly used DJ equipment throughout our house, who’s to say?

For all the dumb and lamentable things that exist in the world only because of cocaine, there is a remarkable amount of great music that probably would never have been recorded without it. Examples include every 1970s David Bowie album starting with Young Americans; the discography of any artist who appeared in The Last Waltz but especially Neil Young; most electronic music; essential rap albums by Ghostface Killah and Clipse; and all 1980s rock songs that had saxophones in them.

By far the biggest album in the “wouldn’t have happened without cocaine” category is Rumours, the blockbuster record released in 1977 by a band called Fleetwood Mac. When it came out, Rumours was the fastest-selling album of all time. It is absolutely packed with classic songs — “Dreams,” “Go Your Own Way,” “The Chain,” “Don’t Stop,” “Gold Dust Woman” — that only belong to the world because the people in the band consumed a shipping container’s worth of powdered drugs while they were writing and recording it. Lindsey Buckingham, Fleetwood Mac’s guitar player and de facto bandleader at the time, was the original Cocaine Bear.

The story of Rumours is an important piece of pop-music mythology. If someone asked an A.I. program to create a screenplay based only on the Wikipedia page for this album, it would be the best rock and roll movie ever made. These people, to borrow a modern term, were on one. Aside from the general atmosphere of mania and excess that characterized the creation of Rumours, most of the members of Fleetwood Mac were “doing it” with each other or people who were associated with the band, often behind the backs of other bandmates, which adds the kind of complexity to a workplace that people usually try to avoid.

The most recognizable members of the band were Mr. Buckingham and a singer named Stevie Nicks, who joined Fleetwood Mac together in the mid-1970s, when they were a romantic couple. There is a whole tangled earlier history of the band that not many people care about. That’s because when Mr. Buckingham and Ms. Nicks joined, the group changed from being a weird British blues act into the soft-rock California sex monsters that people now picture when they hear the name Fleetwood Mac. Their first album with this lineup was Fleetwood Mac, which was released in 1975 and contains a father-daughter song that causes people to stare meaningfully out the nearest window whenever they hear the opening notes.

Mr. Buckingham and Ms. Nicks’s relationship ended while Rumours was being recorded. In general, your dad is violently disinterested in the personal lives of famous people. But in rare cases, their romantic entanglements have specific, profound impacts on the art, and Rumours, in addition to being an exhibit-A cocaine album, represents one of the great bitchy soap operas in the history of rock music. The songs “Go Your Own Way” and “Dreams” are basically Mr. Buckingham and Ms. Nicks telling each other, respectively, to eat shit. They would reenact this drama every night, coked out of their minds, in front of thousands of people when touring to promote their album, and for decades thereafter.

Check out the video from the 1997 concert film The Dance where they sing “Silver Springs” (a song recorded for Rumours but left off the final tracklist) and notice how aggressively they were still eye-boning each other, 20 years after releasing the album inspired by their breakup.

This dynamic would continue, more or less, for another 20 years, before Mr. Buckingham was dismissed from Fleetwood Mac. The band persisted for another few years after that until the singer-songwriter and keyboard player Christine McVie — who looked like she could have been the mom to the group but was just as wild as the rest of them — passed away in 2022. (“Pass away” is a euphemism for dying. We’ll get into that another time.)

All in all, this is a pretty unique set of circumstances for a band. But the story of Fleetwood Mac and Rumours in particular has become shorthand for the difficulty of combining romantic partnership and creative collaboration. Your dad has been in two bands with married couples — one of which was him as the fifth wheel to TWO married couples, and in both cases it was less awkward, tumultuous and extramaritally sexy than he would have anticipated, although those expectations were entirely based on the legend of Fleetwood Mac.

Daisy who and the what now?

The singularity of Fleetwood Mac becomes obvious when you observe the art they have inspired — not just bands who have sounded like Fleetwood Mac, of which there are many, but works of fiction that are openly trying to recreate their story. In the last few years there has been a successful Broadway musical called Stereophonic and a popular streaming series called Daisy Jones and the Six, which was based on a bestselling novel of the same name. Both of these stories are about coed L.A. folk-rock bands in the 1970s making mega-platinum albums while battling substance abuse and navigating inter-band melodrama amongst stock rock-star characters — the megalomaniacal frontman, the bewitching tambourine-wielding hippie, and so on. Sound familiar?

Each soundtrack had some decent songs that were not even close to Rumours-caliber. But the real problem with both of these products, and indeed anything else directly inspired by Fleetwood Mac, has to do with scale. Stereophonic and Daisy Jones feature an era-appropriate amount of sex and drugs, although nowhere near the amount of sex and drugs that Fleetwood Mac likely encountered during a single typical day in their mid-to-late-‘70s prime. So what is the point of retelling the Fleetwood Mac story with less interesting characters, less extreme behavior and less memorable music?

It is hard to imagine fiction more outlandish than what really happened. One time Ms. Nicks got so high she almost went blind. She also sniffed enough coke to burn a hole inside her nose. They did so many drugs during the making of Rumours that white powder “peeled off the walls” of the studio. They were considering thanking their dealer in the album’s liner notes, except the guy was murdered just before the record came out. Everyone in the band was so hopelessly addicted that they couldn’t get through performances during their wildly hedonistic tours without doing “bumps,” which are small amounts of cocaine meant to supplement the dose of cocaine a person has already taken. The band followed up Rumours with Tusk, an insane and even more drug-saturated double album (which has become an object of cool-kid fascination even though the songs pale in comparison.) And the making of Tango in the Night (1987), the band’s last major album, is less steeped in legend but was apparently even more deranged and debauched than that of any record preceding it, which is an astonishing achievement. The band’s drummer, Mick Fleetwood, estimated that he had personally snorted a total of SEVEN MILES of cocaine during his first two decades in the group, an amount that even dedicated users of the drug would consider extravagant.

Go your own way, within reason

Admittedly, it can be difficult to describe the breadth of Fleetwood Mac’s decadence without glamorizing some of that behavior, and they are maybe the wrong people to offer as a cautionary tale about the dangers of excessive drug use — give or take the structural integrity of Ms. Nicks’s septum. Because, in their case, drugs were a driving factor in some of the late 20th century’s most indelible rock music. So if you turn into the next Stevie Nicks, I suppose you can snort all the blow you want. (And yes, you’re correct to point out that the words “snort” and “blow” are oxymoronic when taken literally.) But that is a pretty remote “if.”

The overwhelming majority of people who get into drugs do not end up channeling the resulting mind-state into era-defining music, or into anything productive whatsoever. Quite the opposite, actually. Your dad, again, did a considerable quantity of them, and has little to show for it beyond a few Garageband folders of embarrassing self-recorded music that the world will thankfully never hear. If you do become interested in drugs, I cannot credibly forbid you from doing them, but as your father, I beg you to never ingest an amount of cocaine that needs to be measured in miles, or even kilometers.