It is never too early to start mansplaining music to a girl

Repeat after me: "Their old stuff is better."

If everything goes normally, our daughter will spend a lot of time in her life hearing men explain things to her with impenetrable confidence, whether she wants them to or not. Often, the subject of unsolicited male explanation will be music.

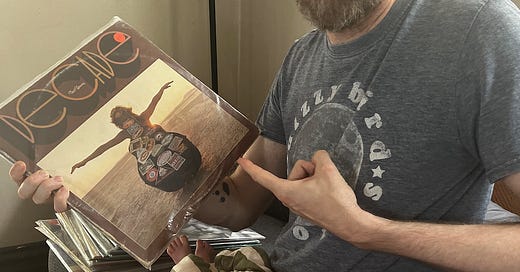

In order to prepare her for this eventuality, and also to acquaint her with the unwieldy record collection she will have to manage after I die, I am taking advantage of her current captive state by talking to (at) her about some of the albums in our library. While circulating recently-played records within the exhaustive system I have devised to organize my listening, I have started to pull aside a few significant LPs to discuss at length with my child, a seven-month-old baby, for what I imagine will be a long-running series of lectures. One day she will surely appreciate this, but for now her awed, passive silence is all the thanks I need.

Below I have paraphrased to the best of my memory some highlights from our most recent session. The terminology here is all hetero/cis-normalized, so pronouns can be adjusted as life unfolds. But I think by now, “mansplaining” is understood as a gender-transcendent concept even if the vast majority of people who do it are still men. Should our daughter ever become involved with a female or nonbinary music-mansplainer, that person will be welcomed into our home with the same mixture of curiosity and incredulity as would the male prototype. Or if she becomes a female music-mansplainer herself, well, I’m swelling with pride just thinking about that.

OK, let’s begin.

Bruce Springsteen: The River (1980)

This is the Boss, whom your dad enjoys but whom your mom resolutely does not. Our views on Bruce Springsteen’s catalog align with standard presumptions about which artists tend to be preferred by men and which are more appealing to women. Gender-based stereotypes are falsely premised in many cases, and you will always find anecdotal counter-examples, but here I think the statistics would generally affirm the conventional wisdom about Mr. Springsteen’s constituency. I don’t know where that data exists. Maybe it doesn’t.

Anyway, this album is called The River, which most fans would agree falls pretty close to the middle of the Boss’s classic period. This is a double album, meaning he included too many songs to fit on a single vinyl record and had to spread it across two. (Don’t worry, in future sessions we’ll get into the physical constraints of various media formats and their downstream effects on the art.)

The theme of The River is the onset of adult responsibility and the youthful resistance to it. He made the album when he was turning 30, which you will think is old until you surpass that age yourself, after which point it seems infuriatingly young. This album contains the thematically representative “Hungry Heart,” which is Dad’s favorite song about a man abandoning his wife and kids for the allure of the itinerant and the unknown. Your own father would never do that, although listen for suspicious phrases such as “I’m going out for cigarettes” or “I have to meet someone from Facebook Marketplace.”

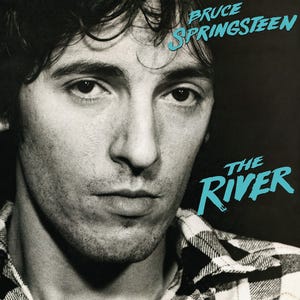

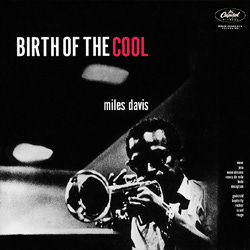

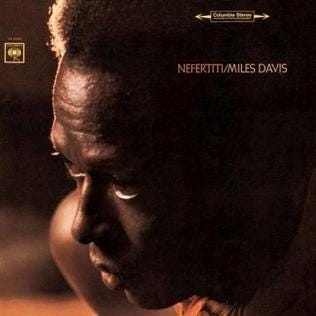

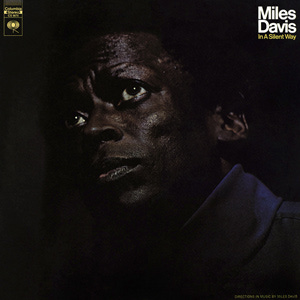

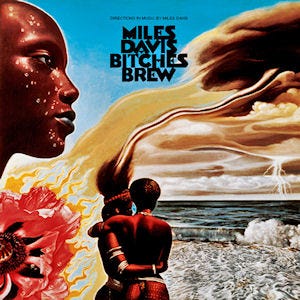

Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool (1957), Kind of Blue (1959), Nefertiti (1968), In a Silent Way (1969), Bitches Brew (1970), Agharta (1975)

Your dad has a lot of Miles Davis records. A lot of jazz records in general, actually. There was a period when he would buy almost any low-priced used jazz album by an artist he recognized, convinced that immersion would enable him to finally “get” what was going on with the music. This effort was unsuccessful.

Jazz is a foundational style of popular music, but also an entire specialized field of expertise, due to its technical complexity relative to other genres. This barrier will not, unfortunately, discourage people from trying to explain it to you, whether they know what they’re talking about or (as is more often the case) not. Be aware that there is usually an inverse relationship between the enthusiasm with which a man explains jazz and the real extent of his knowledge base. You will find that this is true of most music.

However, whether or not you understand what is happening moment to moment, trying to self-educate about jazz, and forming your own unique relationship to it, can still be a lot of fun if you have the time — although with the world we’re leaving you, you’re probably going to be working ten different gig-economy jobs during what would otherwise be your prime music-discovery years, and you won’t have the capacity. Sorry about that. Actually, blame your grandparents.

If you ever want to turn the tables and make a guy’s head explode, casually mention that your favorite music memoir is Miles: The Autobiography, by Mr. Davis himself. It doesn’t matter if this is true. You don’t really need to read books by musicians to appreciate their art, and in some instances you absolutely should not, but if you are interested, this one does contain some amazing Charlie Parker heroin stories.

Massive Attack: Mezzanine (1998)

Massive Attack, a band from the United Kingdom, is among the most popular performers of what became known as “downtempo” electronica. Another term for this is “Elder Millennial Sex Music.” If “Teardrop,” the third track from the album Mezzanine, begins playing in a room full of people your mom and dad’s age, and any of them start making mischievous/affectionate eye contact with each other, it means they have smashed to that song dozens of times.

Funkadelic: Free Your Mind... and Your Ass Will Follow (1970)

This is what music sounds like when the people recording it do cocaine and LSD at the same time.

Fugazi: Repeater (1990)

If you mention Fugazi during a conversation with a man, there is a good chance he will immediately achieve orgasm. This process usually requires genital stimulation (partnered or solo), but for a certain category of heterosexual male, merely hearing a girl speak the word “Fugazi” — pronounced Foo-GAH-zee — will have the same effect.

Should you happen to acquire a sincere interest in any of the countless taxonomic variations of aggressive rock music, Fugazi’s catalog is well worth exploring. Your dad entered backwards via their final album, The Argument, but there’s really no wrong place to start. Repeater kicks ass.

Setting aside what they actually sound like, Fugazi exists in the popular consciousness as the standard-carrier for certain bygone, abstract principles that rock musicians were expected to lionize. Chief among these is that a band should never “sell out.” This is an idea based on dated assumptions about the relationship between economics and art. It meant that artists could receive compensation from some sources but not others, lest they be shamed and ridiculed. The rules about this were inconsistently enforced and historically complicated, but they were premised on the idea that “indie” musicians who reached a certain level of skill and credibility should be able to subsist modestly on proceeds from album sales and live performances as long as they were content to drive shittier cars than their peers in bands who signed major-label recording deals, licensed their songs for placement in advertisements or adapted their music to broaden its commercial appeal.

This was an orthodox position that people believed fiercely until about 2003, after which point it was never mentioned again. Around the turn of the millennium, when your dad was in college, everything about the music business changed, because people figured out how to acquire and distribute albums and songs without paying the normal retail price, through digital downloading and file-sharing. As a result, revenue from CDs disappeared and, along with it, the entire business model that had been sustained by the high profit margins from that format.

Artists, suddenly confronted with a narrower stream of possible income, faced a conundrum: Could they still afford to turn down money from people or organizations that made them uncomfortable? Any band whose song appeared in an ad or a corny soundtrack in the 1990s would have been ostracized (symbolically if not functionally). Starting in the 2000s, however, the same action instead signified shrewd survival instincts, because then the band got enough money to record their next album, which would give them a reason to tour but which nobody would buy. Don’t hate the player, etc.

Fugazi went on permanent hiatus in 2001, which means they never really had to test their much-lauded ethical standards against the brutal conditions of the quickly evolving digital marketplace in real time. They retired with an unblemished legacy of idiosyncratic, non-sellout practices such as DIY distribution, touring without merch and refusing to sell tickets for more than $5, which would barely get you a cup of water at a concert today. The 21st-century version of this worldview would probably require a band to abstain from making its music available to streaming services. Incidentally, if you’d like to check out Fugazi for yourself, their catalog is on Spotify.

Steely Dan: Aja (1977)

If somebody starts a conversation with you about Steely Dan, do not leave a drink unattended in their company. Actually, just call for help.