What 'Lynchian' really means

All of us are dead, wrapped in plastic and existing in David Lynch's America.

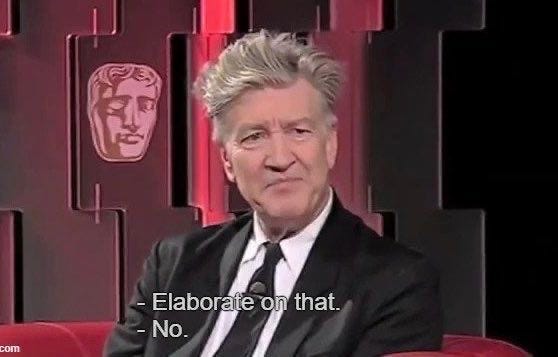

Despite his folksy persona, filmmaker David Lynch was a famously obtuse interview subject, particularly on the topic of what his work “meant.” Anybody who tried to penetrate the visible surface of his material generally ran into a brick wall of awkward silences, monosyllabic non-responses, curt dismissals and tangential excursions. The filmmaker, who died earlier this week at 78, was almost pathologically resistant to any attempt to decode or explain the content of his films in a conventional sense, which frustrated a lot of viewers, understandably, given the opaque and nonlinear nature of even his most popular work. The distance between the profundities a creator appeared to communicate through his art and his personal interest in trying to externally articulate those meanings was wider for Lynch than any modern artist besides perhaps Brian Wilson.

So naturally, the most verbose novelist of his era would be the person you’d assign to “understand” Lynch via a magazine profile. David Foster Wallace, author of the totemic ‘90s novel Infinite Jest and several celebrated works of dense short-form journalism, was allowed onto the set of Lynch’s 1997 L.A.-noir head-fuck Lost Highway on the condition that he not attempt to speak with the filmmaker. His eventual piece for Premiere magazine, “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” which later appeared in the collection A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, nonetheless produced a definition of the oft-deployed adjective “Lynchian” — as in, “in the style of David Lynch” — that’s more succinct and feels more accurate than any attempt I’ve encountered since.

The extent to which something is Lynchian, Wallace noted, is akin to pornography or postmodernism, concepts that are “definable only ostensively — i.e. we know it when we see it.” Yet, he still formulates a working theory that I can quote almost from memory:

“An academic definition of Lynchian might be that the term ‘refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.’”

Many of the tributes that have appeared since Lynch’s death propose variations on this idea. The NY Times obit described his style as “the eroticized derangement of the commonplace.” He produced “images of American innocence and what hid beneath idealized facades of normality” (NPR). His films “made strange things seem normal and normal things feel strange” (Time). His terrain was a landscape of “violent, predatory dreams that seem like the underside of the virtuous myths that Americans eagerly bought” the first time they elected a blundering entertainer to the presidency (New Yorker).

That’s just based on a few minutes of clicking around, but those characterizations feel representative of how Lynch’s work is collectively appraised. However, they seem to miss something Wallace understood: the part about “the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” Lynch’s marriage of gee-whiz Americana and nightmare surrealism wasn’t a juxtaposition or a tonal collision. It was his acknowledgement that these elements are entwined in symbiosis, and that one doesn’t happen without the other. You can’t have the idyllic suburbs without the severed ear rotting on the ground. You can’t have the comfortable middle-class home without Bob crawling over the back of the living-room couch. You can’t have lunch at Winkie’s Diner without the dumpster monster out back ready to deliver the best/worst jump scare of all time (update: holy shit that’s still terrifying). You can’t be elected homecoming queen without your body turning up on a riverbank.

This is surely the subject of a million term papers, but I think this sensibility is what made Lynch the quintessential American filmmaker — that he not only translated a specific dark dream logic to film, but that he made it inseparable from what we could consider ordinary. He intuited certain currents of American reality better than any artist in his medium, gazing unflinchingly into a void that he may have perceived not as a dark underbelly, but maybe just the belly. He helped viewers understand that to live in this country, participate in its commerce, consume its culture, engage in its politics and otherwise embody its quaint idealisms was to manifest its contradictions so seamlessly that they no longer seemed like contradictions.

Consider: The most powerful nation in the history of the planet is literally built on an Indian burial ground. The richest society on Earth extracted staggering wealth from forced labor, to the ongoing enrichment of the ancestors of people who enslaved other human beings. The first modern democracy has so many public mass shootings that they barely qualify as news anymore. The nation with the mightiest military ever assembled has relinquished its influence across decades of imperial misadventure. The world’s hub of industrial innovation and technological progress denies its citizens healthcare as an essential human right. The first nation to put a man on the moon incarcerates more people than any other country on Earth. The society that invented jazz and baseball and the iPhone also perpetuates sickening levels of economic inequality and structural deprivation. The country that fought a revolution against tyranny and produced the Bill of Rights later voted to instigate their own descent into autocratic oblivion.

This is America: For every pie cooling on a windowsill, there are a hundred murdered indigenous people. For every bountiful Thanksgiving feast, a person sleeps on a sidewalk. For every inspiring Fourth of July fireworks display, a family is separated at the southern border. For every first kiss at a high school prom, an Afghan wedding is decimated by an American cruise missile. For every inspiring gold-medal performance by a U.S. Olympian, a woman in a red state is denied reproductive healthcare. For every potluck in a church basement, a Black teenager’s life is ruined by incidental contact with the law-enforcement system. For every disadvantaged kid who bootstraps their way to a college scholarship, a toddler in Gaza is blown to pieces by a bomb that falls in the name of the American taxpayer.

We’re all wrapped in plastic

Wallace went on to admit that “Lynch’s movies’ deconstruction of of this weird ‘irony of the banal’ has affected the way I see and organize the world,” then lists several real-life examples of things he would consider “Lynchian”: the Jeffrey Dahmer murders, most of the people who congregate in city bus terminals late at night, the assumption of a grotesque facial expression that freezes in place for longer than circumstances warrant. These things do seem to fit the description, but whether we consciously “see and organize the world” according to our understanding of Lynch’s overarching aesthetic, we have already achieved a purely Lynchian condition simply by existing today in the United States of America.