The right’s cancellation narrative is so full of shit

Ask Paul Reubens what it really means to have your life destroyed in a witch hunt

The top-selling album in America right now is I’m the Problem, by the country star Morgan Wallen. About 30 of its way too many songs are currently on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, three of them in the top five. This is a remarkable achievement for any artist, particularly one such as Wallen, who, you might recall, got canceled a few years ago.

Wallen in 2021 was recorded using the N-word while drunk. When a video of the moment leaked, the industry responded swiftly. Wallen’s music was pulled from country radio and streaming playlists. His record label suspended his contract, and his new album at the time, Dangerous, was declared ineligible for the following year’s Country Music Awards. Wallen performed the standard exercises in public contrition: apologies, donations, counseling, “doing the work.” He posted a remorseful video asking fans not to defend his actions. The listening public, in an era when popular culture was undergoing an overdue reckoning over racism in the music world generally and country music in particular, was quick to make an example of Wallen.

What kind of example? Country listeners were so outraged at Wallen that physical and digital sales of Dangerous doubled within a week of the incident and sales of his back catalog soared. Dangerous became the top-selling release of 2021, and each of Wallen’s subsequent albums has been a blockbuster.

Wallen’s 2023 single “Last Night” spent 16 non-consecutive weeks atop the Billboard pop singles chart. That same year, the country artist Jason Aldean released “Try That In a Small Town,” a very dumb culture-war anthem that, as the title suggests, inserted itself into the perceived moral and political schism between big cities and small towns in America. The track became controversial following the release of a music video that Aldean filmed at the site of an infamous lynching of a Black man in the 1920s. The ensuing outcry prompted Aldean to tell an audience from the stage at a concert in Cincinnati (not a small town): “Cancel culture is a thing. If people don’t like what you say, they try and make sure they can cancel you, which means try and ruin your life, ruin everything.”

Yeah, do they, though? Following the controversy over its video, “Try That In a Small Town” climbed to the top of the Billboard charts, where it briefly interrupted the near-record reign of “Last Night,” a track by an artist whose own blacklisting by mobs of social justice keyboard warriors has turned him into arguably the biggest figure in American pop music apart from Taylor Swift. Thoughts and prayers to those poor canceled dudes.

Try that in a small-town porn theater

While “Last Night” was enjoying its chart-topping run in the summer of 2023, Paul Reubens, an actor and comedic performer best known for creating the beloved Pee-Wee Herman character, died of cancer at age 69. Reubens is now the subject of Pee-Wee as Himself, a documentary on HBO Max that explores his work, his complicated legacy, the tragic details of his fall from grace and his attempts to rebuild his life and career in the aftermath of an actual cancellation.

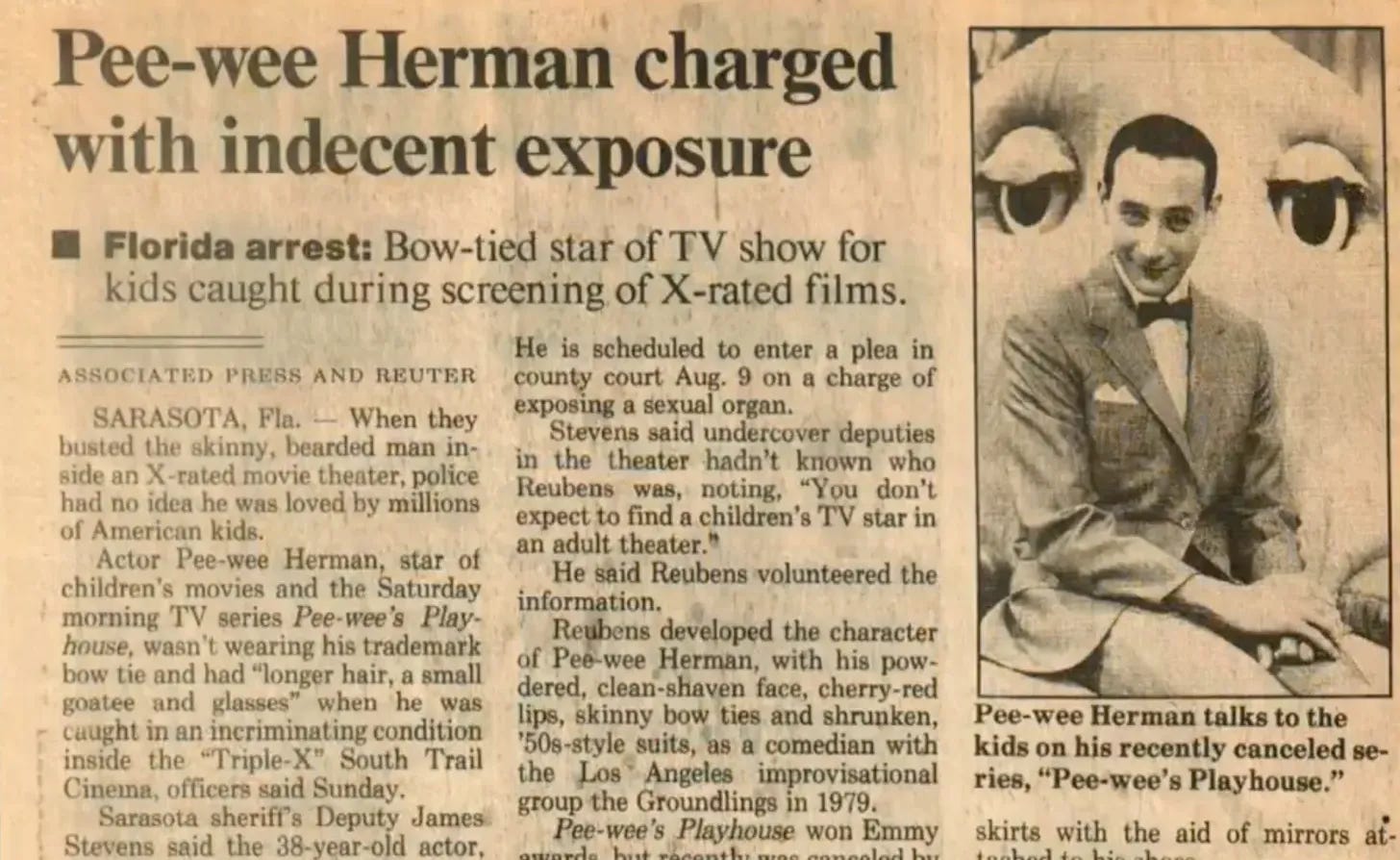

In 1991, Reubens, star of the popular kids’ show Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, was arrested in Florida for indecent exposure in a porn theater. This was huge news at the time, since the alleged crime was so sharply at odds with Reubens’ image as a beloved children’s entertainer.

It is hard to overstate Pee-Wee’s importance to kids of a certain generation. Reubens developed the persona as a riff on 1950s children’s programming while he was a member of the Groundlings comedy troupe, turning Pee-Wee into a successful stage act and talk-show mainstay. Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, the debut film from director Tim Burton, was a surprise hit in 1985 and has aged into a classic. (My family still teases me for how badly the Large Marge jump-scare freaked me out as a kid.)

The film’s success led to Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, which in retrospect was a strange project: an actual kids’ show based on a character who was a parody of a kids’-show star. Even more unusual at the time, it was Saturday-morning kids’ entertainment that didn’t talk down to its target audience, while delivering enough witty surrealism, postmodern self-awareness and subversive queer coding to captivate even the edgiest adults. The playhouse was a luminously weird space where every oddball was welcomed with no mandate but to be silly, sincere and decent. It was a cheerful realm where anthropomorphic household items — Chairry, Globey, Mr. Window, etc. — were as full of life as the diverse cast of humans that came and went. As Reubens explains in the documentary, directed by Matt Wolf, his mission was to create a radically inclusive environment and then make no comment on it whatsoever.

The result was a character who became a rare consensus figure in pop culture, beloved by critics and the public alike. As Reubens explains in the film: “There wasn’t a moment in the ‘80s where it wasn’t super-cool to be me.”

What could possibly happen next?

The man behind the red bow tie, however, was inscrutable. Reubens never did interviews out of character and was by all accounts (including his own) a control freak. He guarded his privacy fiercely, wearing disguises in public and dodging questions about his personal life, which prompted widespread speculation about his sexuality. Reubens never came out publicly, but Pee-Wee as Himself details a formative relationship with another man early in his adult life, preceding his career in show-business, and later reveals that he was in a relationship at the end of his life, but does not identify the partner.

Reubens sat with Wolf for 40 hours of interviews in the years before his death from a cancer that he had not disclosed to the public or the filmmaker. The project appears in two 90-minute halves, the first of which charts his years as a performance artist and the development of Pee-Wee from an obscure sketch character into a national media phenomenon. The second half is…everything else.

The details of Reubens’s arrest were, to put it generously, pretty sus. He was in Sarasota, which is where he grew up and where his family still lived, taking a break after he had filmed the final two seasons of Playhouse. (He had already decided to retire the Pee-Wee character.) Four officers from the local sheriff’s department were undercover at a destitute, otherwise mostly empty adult-film parlor on the outskirts of the city, where they said they observed Reubens masturbating and apprehended him.

Later reporting found that the police had spent five or six hours in the theater (hmm), and on the night of Reubens’ arrest they had threatened to cite an employee for obstruction of justice if he tried to warn customers of their presence. Sarasota vice cops were apparently famous for their excesses; an extensive piece in Sarasota Magazine notes that the local PD had already made recent national headlines for arresting beachgoers whose bathings suits were too revealing.

A 1991 Rolling Stone story argued that the officers’ actions reeked of entrapment, even if they weren’t targeting Reubens specifically. A local lawyer told the magazine that arresting adults for masturbating in an adult theater “was like the vice squad going into an alcohol-rehabilitation center with a pitcher of martinis and saying, ‘Who wants a drink?’”

Also, those kinds of theaters were a little before my time, so pardon my ignorance, but what were they for if not…that? If there was nobody else there besides a few customers who were apparently outnumbered by cops, what harm was being done, and what public good was served by sending in the cavalry?

In any case, a local reporter recognized Reubens’ name in the police blotter. The story ran and quickly went national. The actor experienced the early-‘90s version of viral infamy, which meant news segments, late-night TV jokes and his incognito mugshot plastered all over the supermarket tabloids. CBS pulled reruns of Pee Wee’s Playhouse and Reubens went into hiding.

I know you are (a bunch of assholes) but what am I?

The national media reacted with an intensity that was fueled by misinformation, prejudice and old-fashioned moral hysteria. Newspapers ran syndicated stories advising parents how to talk to their children about Pee-Wee. Daytime talk show segments falsely equated Reubens’ private actions with the abuse of children. A detailed analysis of the media coverage showed that people who were kids at the time disproportionately misremembered Reubens’ arrest as having something to do with pedophilia, or at least lewd behavior at a regular movie theater.

At the time, Reubens was preparing for a creative life beyond his iconic character. But the uproar made that nearly impossible, even though almost everybody who looked at the details of the case thought the cops were overzealous and agreed Reubens would have been acquitted if he went to trial. Any substantive piece of reporting on the case ended up being sympathetic to Reubens purely on the basis of the facts. It is unclear how the court of public opinion might have treated him if he had fought the charge, but there is reason to believe he could have been vindicated. Six weeks after his arrest, MTV invited Reubens to open the 1991 Video Music Awards in character as Pee-Wee, where he was received joyously by an audience that had grown up with him and still loved him. But Reubens ended up taking a plea deal, hoping it would make the whole thing go away. It never did.

He re-emerged tentatively throughout the ‘90s, appearing in supporting roles in big films such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Batman Returns, Mystery Men, Blow — but in 2002 was arrested on a more serious charge: suspected possession of child pornography. He pleaded down to a lesser obscenity offense when it was determined that the images Reubens possessed — uncovered while police were investigating another performer, the “yup, he definitely looks guilty” actor Jeffrey Jones — were part of a collection of vintage erotica and kitsch memorabilia.

Pee-Wee as Himself becomes uncomfortable as it moves through this later period. During the first three-quarters of the documentary, Reubens comes across as warm, self-effacing and in on every joke about his dramatic rise and fall. He banters with Wolf about his trustworthiness, his anxiety about how he’ll be presented and the ethics of the relationship between interviewer and subject. It sounds lighthearted; later on, though, it becomes clear that the anxiety wasn’t part of the act.

He stopped participating in the film and would not be interviewed about the later arrest, but he sent Wolf a voice message the day before he died. Over the film’s closing images, we hear Reubens speak in a weakened voice: “More than anything, the reason I wanted to make a documentary was for people to see who I really am, and how painful and dreadful it was to be labeled something I wasn’t.”

Admittedly, this part of the story adds complexity to a creative legacy — including a sadly overlooked Pee-Wee reboot movie from 2016 — that never got the reappraisal it deserved while he was alive. But Reubens, to his last breath, was fighting to regain control of a narrative that had been yanked away decades earlier.

The secret word is “hypocrisy”

The documentary offers a simple reason for why that happened: Reubens was gay. His adult life deviated from the norm, and he had to be destroyed because of it. “This was a homophobic witch hunt,” a publicist tells Wolf about Reubens’ later arrest, which was the work of a politically ambitious city attorney on a moral crusade that had a familiar smell to it.

People who grew up in the 1980s and ‘90s remember who was usually on the receiving end of what we now call cancellation, and it wasn’t artists who were insufficiently “woke.” It was people whose personal behavior seemed to reinforce a specific right-wing narrative about our culture’s supposed godless depravity.

The Reagan-era rightward realignment of American politics in the ‘80s coincided with the growth of the Moral Majority and other combative evangelical groups in direct response to the civil-rights gains of the ‘60s and ‘70s. In the fevered collective imagination of the religious right, every progressive social achievement happened at the expense of traditional Christian values and could only be symptomatic of a wider cultural decay. An increasingly secular, pluralistic society supplied an endless array of enemies necessary to sustain a profitable fundamentalist fervor: academia, feminism, mainstream media, Hollywood, pro-choice activists, social-welfare recipients, gay-rights supporters and so on.

In practice this meant protesting Disney for providing benefits to the same-sex partners of employees, boycotting the Teletubbies for who the fuck remembers what reason, targeting retailers for saying “happy holidays” instead of “merry Christmas,” stigmatizing popular musicians for impure lyrics, leading actual book burnings in church youth groups and, of course, shaming any public figure whose personal conduct diverged from the narrowest possible definition of moral correctness. Today, as the “woke” era recedes into the past, cancellation means laws banning drag shows, removing “obscene” books from public libraries and efforts to criminalize abortion care and youth gender medicine.

Watching Pee-Wee as Himself makes it a little difficult, then, to feel sorry for country artists getting yelled at online. As Jonathan Merritt wrote in 2020 for the Religion News Service, conservative targets of so-called cancellation have never been “victims of a liberal culture out to obliterate them from acceptable society; they are the collateral damage of a culture they helped create. They are reaping what they have sowed.” So anytime you hear someone on the right bitching about being persecuted, perhaps while selling millions of records, just remember that they built the cross themselves.