‘Love You Forever’ is even more disturbing than everyone says

“As long as I’m living, your waking nightmare I'll be.”

There is a rich tradition in children’s literature of stories that are meant to disturb their target audience, gently or otherwise — your Roald Dahls, Edward Goreys, Hans Christian Andersens, etc. Far more interesting, however, are kids’ books that are sincere but inadvertently upsetting to adults. Think, for instance, of that page in Goodnight Moon that just says “Goodnight nobody.” Or the minor Dr. Seuss classic There’s a Wocket in My Pocket, in which a young child is terrorized by a creature called a Vug, which exists as a lump underneath a rug but is otherwise unseen. Or the end of The Giving Tree, where that greedy bastard of a boy has grown old and rests his bones on the dead stump of the friend who has already thanklessly given him everything else and can now offer only a depleted corpse.

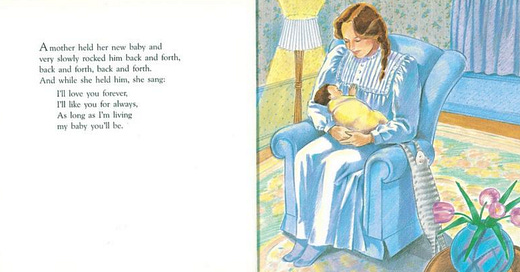

The most divisive work in this latter category has to be Love You Forever, the 1986 picture book written by Robert Munsch and illustrated by Sheila McGraw. This story, about the lifelong bond between a mother and her son, is beloved, reportedly having sold 38 million copies since its publication almost 40 years ago. It appears regularly on rankings of all-time favorite children’s books and is referenced from time to time in pop culture, thanks mostly to an oft-repeated passage that has become rightly famous:

“I’ll love you forever,

I’ll like you for always,

As long I’m living

my baby you’ll be.”

Even people who don’t know the whole book will recognize these lines, which appear in Etsy home decor, in an emotional reading from a Friends episode and (naturally) in millennial tattoo art.

The story is about a young mother — perhaps single; it doesn’t say — who rocks her sleeping baby while reciting that verse. At night, the mother checks in on him, crawling across the floor of his nursery so as not to disturb him, peeking over the edge of his bed to make sure he’s asleep, then cradling him again in her arms and repeating those cherished lines: “I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always. As long as I’m living, my baby you’ll be.” The baby grows, first into a rambunctious toddler, then a headstrong 9-year-old, then a rebellious teen, and at each phase, the mother performs the same act: cradling her sleeping son and reminding him of her enduring love.

She even repeats this process after the boy has moved away, and the son later completes a full circle by returning the gesture when the mother becomes sick. One of the final images shows him in a rocking chair, holding his aging mother in both arms and speaking the verse that she is unable to finish on her own: “As long as I’m living, my Mommy you’ll be.”

You’d have to be a monster not to be moved by this on some level, especially considering the backstory of the book, which Munsch wrote while he and his wife were grieving two babies who were stillborn.

And yet, Love You Forever provokes intense reactions. Many interpret it as a straightforward, tender presentation of a mother’s devotion, but plenty of readers find it intensely off-putting. “Either it moves you to tears and you love it, or it makes your skin crawl and you detest it,” says a representative description from Publishers Weekly. Lots of people find it “unhinged,” emotionally manipulative and even sinister. Apparently this debate has raged for decades and seems to enjoy a moment of visibility every couple of years — most recently in 2024, after a prominent mom-fluencer reignited the argument with a viral social post that blasphemously declared: “I hate Love You Forever.”

The consensus among the haters is that there is something not right about the mother. Throughout the story, she displays an alarming lack of judgment and an inability to establish or maintain reasonable, healthy boundaries with her son. And just on a practical level, it is utter madness to risk waking up an already-sleeping child — particularly an infant or toddler — just to indulge in a moment of parental warmth. A sleeping baby is adorable, but also a lot like the T-Rex in Jurassic Park, insofar as making any perceptible movement in its presence is gambling with your own life. A parent who has just successfully gotten a child to sleep is far likelier to spend that time doing one of the many things they were unable to accomplish while the baby was awake, such as catching up on housework, exercising, reading a book, drinking wine directly from the box or staring mournfully into the distance.

Anyway, as the boy grows, this ritual unfolds in ways that are increasingly bizarre and suggest a toxic codependency, which manifests most troublingly in the climactic scene where the mother drives to the son’s house, with a ladder strapped to the roof of her car, to let herself uninvited into his bedroom in the middle of the night.

Once inside, she cradles him and whispers those indelible words: “I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always. As long as I’m living, my baby you’ll be.”

This is where the readership divides into two lanes of interpretation. Lane one: The mom’s attachment to her son is cute and almost certainly allegorical (if exaggerated), and the book ends as a tender meditation on the perseverance of love across time and distance and generations. Lane two: Jesus Christ, this is creepy.

There was no reason the mom couldn’t have achieved similarly meaningful contact after first talking to her son before making the drive (with, again, a ladder) or at the very least, knocking on his door. Her lack of self-awareness about the violation of her son’s autonomy undermines the entire premise of Love You Forever. However strong their attachment early in the child’s life, the relationship has since metastasized into something deeply unhealthy. By the time he’s reached adulthood, the son has no doubt been subjected to many iterations of this experience, and his tolerance of it, whether enthusiastic or begrudging, is just giving oxygen to whatever is broken inside the mom.

To some extent, the book’s polarized reception simply reflects how the popular understanding of parent-child bonds has evolved, which means there can be a reasonable middle position. Readers could acknowledge the sweetness of “I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always…” while also recognizing that a lot of things have changed since the book appeared, which was long before most parents actively acknowledged the existence of a child’s interior life, agency, need for mental/physical autonomy, worthiness of privacy, etc. (Or maybe that was just my experience of a 1980s childhood.)

And other issues that might have been prevented by purchasing a baby monitor

The violation of personal boundaries, though, is not the thing I find most upsetting about Love You Forever. That would be the part about the mother entering through the bedroom window and crawling across the floor and then into her son’s bed. Maybe I’ve seen too many horror movies with Freudian subtexts, but that idea is just unshakably chilling.

McGraw’s illustrations only show two flickers of this event, but both are disconcerting, more so in their banality than their overt creepiness. Here she is on her hands and knees peering through her sleeping son’s bedroom door, getting ready to approach his bed.

And here she is on an earlier page, looking at her sleeping son once she has reached his bedside. I may be projecting, but don’t her eyes seem a little bit more blackened-in than they should be?

The only image from the mother’s home visit is the peaceful moment in which she lovingly rocks her large adult son, whom she somehow has managed to pick up and maneuver onto her lap without waking:

Here is how the events preceding that moment are described (emphasis mine, because good lord):

“If all the lights in her son’s house

were out, she opened his bedroom

window, crawled across the floor,

and looked up over the side of his bed.

If that great big man was really

asleep she picked him up and rocked

him back and forth, back and forth,

back and forth.

And while she rocked him, she sang:I’ll love you forever,

I’ll like you for always,

As long as I’m living

my baby you’ll be.”

I’m sorry, but what kind of Hereditary-ass shit is THAT? What happens next, does she creep across the ceiling above his bed and then slowly turn her head around like the Trainspotting baby?

I can understand crawling across the floor on your hands and knees if you want to check on a sleeping infant, although taking off your shoes and just walking quietly would also accomplish this? And then, sure, go ahead and do it playfully at some later stages in childhood if it becomes a cute inside joke between the mom and son. But here, to recap, she drives across town, ascends a ladder to the second story of the house he owns as an independent adult, opens the window, squeezes through it, crawls across his bedroom floor to his bed, checks to see if he’s asleep, then climbs into his bed, repeating the love mantra as she cradles the son, who sleeps alone with a cat, for reasons that I’m sure are entirely unrelated to this formative dynamic.

What if the son were to wake up at any point during that process? Would he be appalled at both the transgression and its nightmarish execution? Or would it be routine? “Oh, it’s just Mother, dragging her withered body across the floor of my bedroom in the middle of the night like some ghost out of Japanese folklore.” Does she leave through the window, or does she do a backwards crab-walk down the stairs like the girl from The Exorcist?

It is revealed on the final page that the boy has become the father of a baby girl, to whom he now repeats the “I’ll love you forever” verse. Curiously, though, there is no evidence of a spouse or co-parent anywhere in the house. Did they get murdered in their sleep by the home-invading mother-demon? Or did they just skip town after all of the unexamined Oedipal baggage became too much to handle? Dealing with a mother-in-law is complicated enough already without the real possibility that you will wake up in the middle of the night to find her in your bedroom, watching you in bed.

Some defenders of the book suggest the story is a Rorschach test about a person’s connection with their own mother. If this bond is healthy, the reader will be most responsive to the story’s sentimental elements. If it’s a difficult relationship, the troubling overtones of the mother-son dynamic in Love You Forever will be what their mind attaches to. That could be true in a general sense, but I dunno. I feel OK about my relationship with my own mom; however, the idea of her crawling across the floor toward my bed in the middle of the night, no matter how old I am or whose house I’m sleeping in, is still an image I’d like to microwave out of my brain immediately.

‘Love You Forever & I’ll Call Before I Come Over’

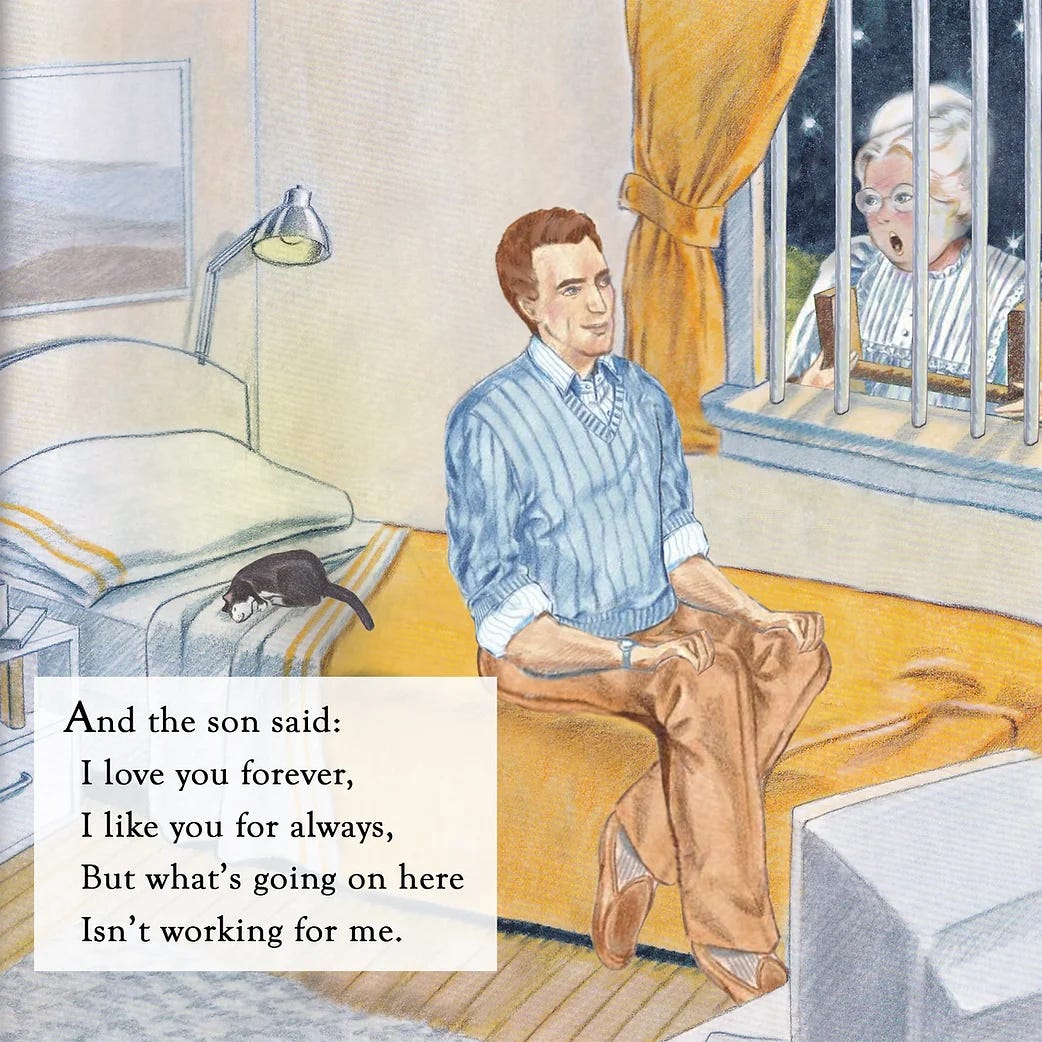

Obviously I’m not the first person to be unsettled by Love You Forever. A writer named Topher Payne created a very funny update to the text that both addresses the creepiness and reflects the changes in social mores that have rendered the original work so controversial. Payne’s revised version is titled Love You Forever & I’ll Call Before I Come Over. When the mother climbs the ladder to her son’s window, she discovers he’s installed security bars:

The man still loves his mom, so they reach an agreement that sounds almost too sensible to believe: She will contact him before coming over, and having obtained permission, will enter his house at the agreed-upon time. They will then enjoy a predetermined activity together, such as taking a walk or seeing a movie. In exchange for honoring this boundary, the mom gets a more edifying relationship with her son. The revised story ends with the man texting her: I’ll love you forever, I’ll like you for always. As long as I’m living, my Mommy you’ll be.”

The benefits to this arrangement are mutual. The mother doesn’t have to use a ladder in her advancing age. Nor must she be on her deathbed before her loving words are reciprocated. And the son gets to have a life that doesn’t feel like a prequel to Psycho.